Syracuse, New York.

October

20th, 1909.

My

dear Mrs. Verrill:-

How I wish you might have been with me this summer

while I spent five days in the charming little English village which bears our

name. They call it in Yorkshire the

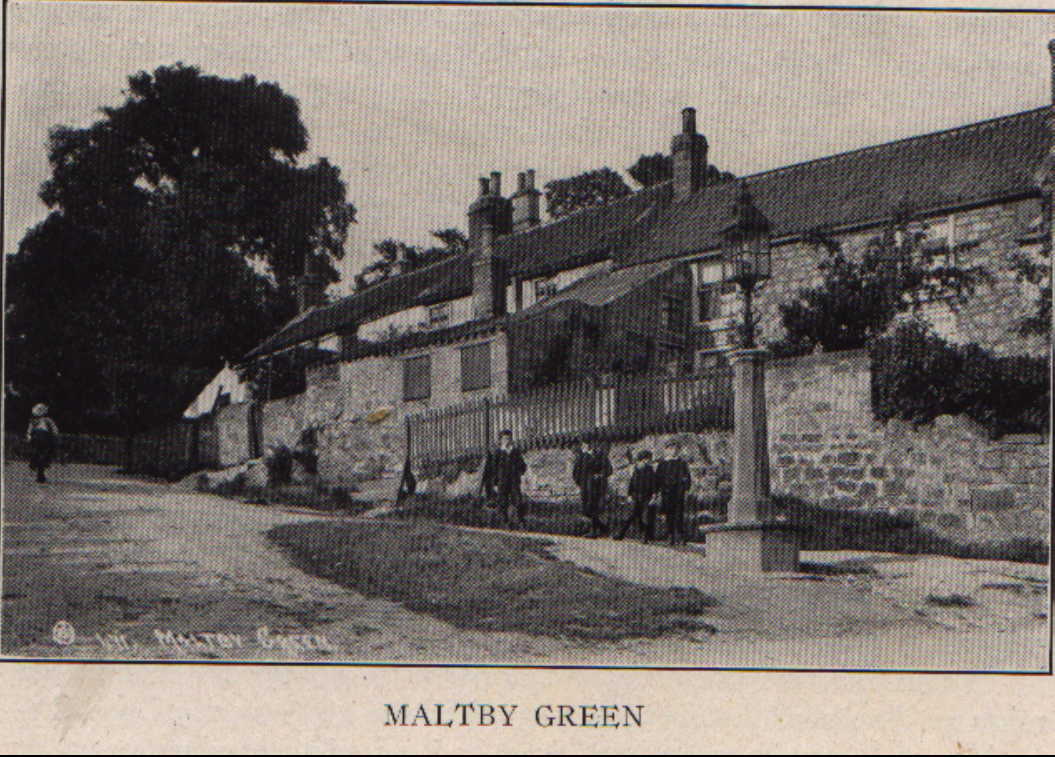

“Quean of Villages.” It deserves the

title! So quaint and

interesting, preserving all the characteristics of a typical old-time English

story-book town.

First I must tell you that when I was in Chester, the

people in the hotel on hearing my name at once said, “There is a Maltby in our

long-distance ‘phone book,” and I had them call them for me, just for fun, at Rhye, down on the west coast of England. Such astonished people as they were to know

that a Maltbie from America was on her way to Maltby in England. They were evidently plain people; the man,

who is a butcher was not there, but his wife, with

whom I spoke was as pleasant as could be but knew very little about the

family. They were the only people of the

name I heard of in England.

From Chester I went to York and from York back to Rotherham. In the

book shops there I found beautiful postcards of Maltby

and its surroundings. From there, while

I waited for the quaint old lumbering bus, which runs on certain days to my

dear little town, I took trams, first to huge and dirty Sheffield. It is like Pittsburge. Then to Masboro, a

pretty little suburb of Rotherham, Rotherham itself has an interesting history. All the country thereabouts has, from Chester

and York with their old walls and gates and cathedrals and towers to “Scrooby, ten miles or so the other side of Maltby where

Elder Brewster was born and the first Pilgrim church organized.

I left my friends in York and went to Maltby

alone. It was quite an adventure. If you could have seen that old stage (looked

like a “prairie schooner”) with seats along the sides and old ladies and

baskets and boxes and bundles all crowded in together. One had to go to an old inn yard in Rotherham to wait for the stage driver to “poot oot the horses.” I heard real Yorkshire dialect there, driving

out. There were five old ladies, one

small boy, the driver, piles of luggage and myself. If was so funny when we rattled up the queer

old-fashioned street, out of the inn yard where hung the old lamp and the

arms-everything seemed unreal-and far from the busy world.

The old ladies wore silk mantillas (I think that is it) and bonnets like this.

(We regret we can not here reproduce Miss Maltbie’s clever marginal illustration of the type of old

ladies.)

They all had volumes to say about Maltby, but had

never heard of a person of the name.

They wanted to know all about American.

When we stopped at other little villages along the seven-mile drive to

Maltby, out came from this inn or that, a pretty barmaid (just like Dickens) to

take your order for a “wee glass ma’am.”

The old ladies took something as a matter of course, but I went thirsty,

through I did have two or three glasses of English ale in Maltby. The small boy told me all about his home and

the chickens he was raising and about the queer piece of American money-a

cent-he owned. He and I sat on the box

seat and “Jawhnny,” the driver, told us about the

country places as we went along, in such a broad dialect, I had to listen with

all my mind as well as my ears to understand.

Fancy how entertained I was with it all and especially when “Jawhnny” informed me that the “American chilled ploo (plough) ware na goot-toorned te

ert opp taw mooch.”

Note-“Turned the earth up too much.” We believe that the English do not plough as

deep as we do int eh States, as the climate is not so

severe and it is not necessary.

You see the “chilled plough” is made here in Syracuse

by an old friend of my mother’s. I told

my Yorkshire friend I’d tell Mr. Chase he didn’t like the ploughs.

When we reached Maltby the old ladies vied with one

another in suggesting what I should do for a boarding place. Wanted me to stay with them, but I went to

the “White Swan Inn.” It has been there

five hundred years. Mr. and Mrs. Bishop,

the landlord and his wife, were so nice and did everything to make my stay

pleasant and interesting. Mr. Bishop is

an ex-English soldier, invalided home from the Boer War, but pretty well now.

A huge fire in the diningroom

fireplace cheered and warned me, for I was cold that August evening. It was all just a picture. Mrs. Bishop just took care of me. She has Irish blood and consequently the

delightful and winning ways that come with it.

Though they have a gas plant which lights the larger rooms down stairs,

I went to my room with its pretty fireplace by candle light-much nicer. It was a strange sensation and seemed almost

like getting home. You see I am doubly

Maltbie, because both my father and mother were Maltbies;

so if there is anything in the call of the blood I ought to have felt it

there-and I did.

If you have ever gone rapidly from place to place for

almost three months, seeing daily the most wonderful sights, historical and

artistic as well as Nature’s own marvelous pictures of peoples and countries,

you know how welcome is a halt. I cannot tell you how glad I was to be far away

from trams and trains and busy crowds and just rest and do nothing some of the

time there in peaceful little Maltby.

Sunday morning I went to the historic church and

listened to a sermon given to a small handful of people. But what I most enjoyed was wandering about

the church and churchyard by myself. The

sexton, of course, got out all the records in the little tin box Miss Martha

Maltby speaks of, and we could make out Latin records back of 1600. However, at that time most of the people were

simply spoken of as John de Maltby or Jane de Maltby, no surnames given. It cannot be proven who were

Maltby by name or who just so and so of Maltby. After the records began to be in English it

was easy to read but in the memory of the oldest inhabitant no Maltby has lived

there or been buried there. The church ws burned once and many records destroyed, and these old

parchment books are not being carefully preserved. In the city of York, duplicates would

possibly be found…. Miss Maltbie here tells of her trip, she visited ten

countries, and found them all “wonderfully interesting, but England was home.”

To return to Maltby.

Mr. and Mrs. Bishop owned five “blue ribbon” English carts and ponies

and they drove me miles (one day twenty-five) over those perfect pavement-like

English country roads to Old Cote and Scrooby, where

we lunched, then on to Bawtry, two miles from Scrooby. It was Johnathan Maltby of Bawtry whose

name I remember seeing in our large Genealogy.

It is an attractive town and so near to Scrooby where Elder Brewster lived and preached that no

doubt our ancestors knew those old Scrooby Pilgramites. They

were repairing the old Scrooby Manor, where Elder

Brewster was born, and the woman who lives there now gave me a piece of the old

oak beam. I treasure it, I assure you.

Back of this very old building (It was originally

some five hundred years ago, a Catholic monastery: think of the irony of fate

which made it the home of the Pilgrim church) is a little creek which flows

into the River Trent, and down that creek and river floated the Pilgrims and

thence across the English Channel to Leyden and so to

America. We had not time in Bawtry to look up church records for the Maltby name, but

the Bishops have a promised me they will go and do it some time. Then we went to Canisboro

and Tickhill-where are the old castles-and Stone,

another village. Another day I walked

over to Roche Abbey, over the stone and wooden stiles, along Maltby Crags,

through the beautiful Norwoods and back around by the

road. A five mile

tramp. Some people I met got the

“History of Roche Abbey” from the Rotherham safe for

me to read. It tells in that, that all

that land was held by the Earl of Merton, brother of William the Conqueror: he

also held much land in Lincolnshire and there, is a town of Maltby there. Do you suppose there is any connection in

these facts?

Maltby is on the direct road from London to

York. Dozens of automobiles fly through

and scores of cycles, motor and otherwise.

Most of them stop at the White Swan for rest or refreshment. Roche Abbey, which Lord Scarborough keeps

open on certain days, is an objective point for many parties from Sheffield, Rotherham and Doncaster. Several

wealthy people from these cities have summer homes in Maltby. You know, of course, that the stone for the

Houses of Parliament in London, was brought from one

of the many fine quarries at Maltby. Now

they are mining coal on Lord Scarborough’s estate and speculators plan to

remodel the cunning place. It is a

shame, but the “love of money is the root of all evil.”

Two railroads are near to Maltby now. One station two miles and another

a mile and a half. No passenger

trains yet, but there will be in time and our quaint little place will all be

changed.

You have no idea how strange to seemed

to see my name on the mile posts all over the country of Yorkshire. Just see the length of the letter-and still I

could tell you more.

If any of the Maltby family want to see our quaint

little Maltby town still unspoiled, let them hurry over to England, for in a

year or two many changes are going to take place there and much of the charm wil be gone.

I forgot to tell you – I went to the grammar school

and the children recited for me. The

first hour of the day is given to the study of the catechism. Isn’t that English?

Yours

most sincerely,

Marion Davenport Maltbie.

A DRIVE TO

MALTBY, YORKSHIRE

Rotherham, 17 June, 1910

….. Rotterham is indeed a dull place, but I bound that not

eight miles distant was the village of Maltby, and a

mile further on, Roche Abbey, so I have something besides Durham Palace about

which to write ….

We arrived in Rotherham

Sunday, at 1:30 P.M., and after dinner Neavar

suggested a drive, it being a beautiful day.

So he rented a horse and trap and we drove to Daltan

Village. Here we stopped at the

farmhouse and drank some fresh milk and ate some tea cakes. Then, returning to town by a different route,

I noticed a signboard which read, “7 miles to Maltby.” That settled it! We must go to Maltby: but it was too late to

go so far, so we set Thursday for our “excursion” into the past.

Yesterday being the appointed day (and a lovely June

day, too) we set out for Maltby with the same horse and trap; and what a fine

drive, up hill and down, past green meadows with buttercups and through tiny

old-fashioned villages. At last we came

to Maltby – the prettiest old village of all – the Parish church nestling down

in the valley, just like the picture postcard I sent you. I wanted to see the

church register and records but the clerk was not in the village, so I left,

disappointed in that respect. When you

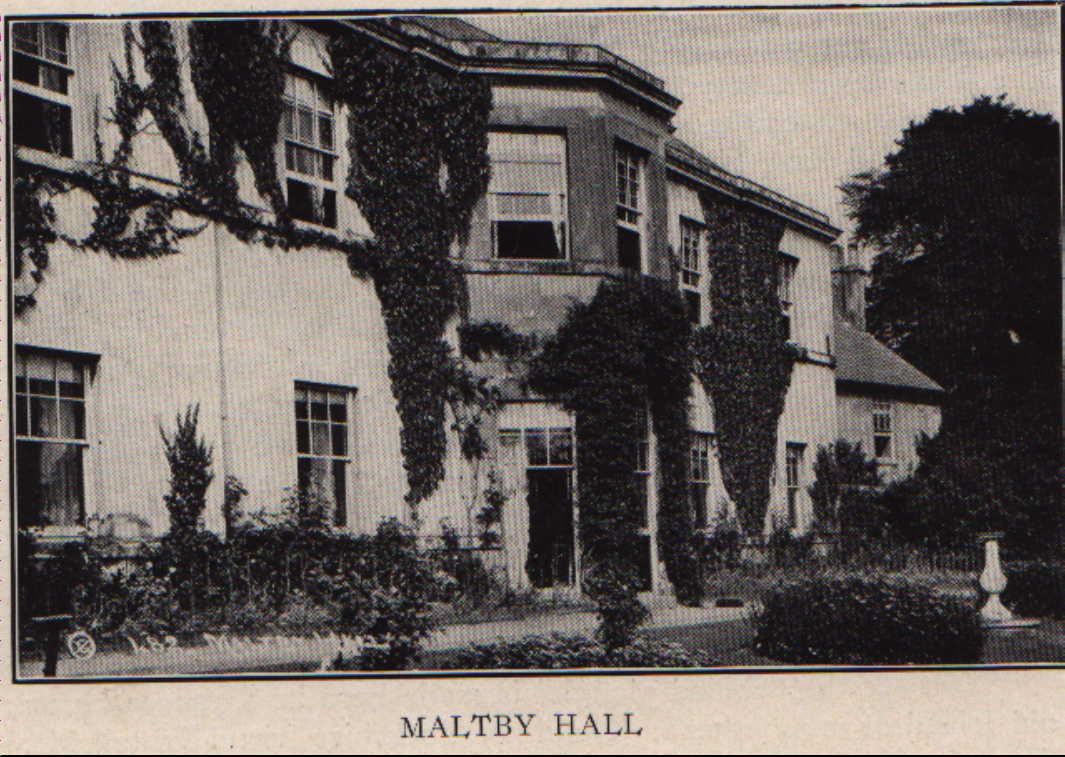

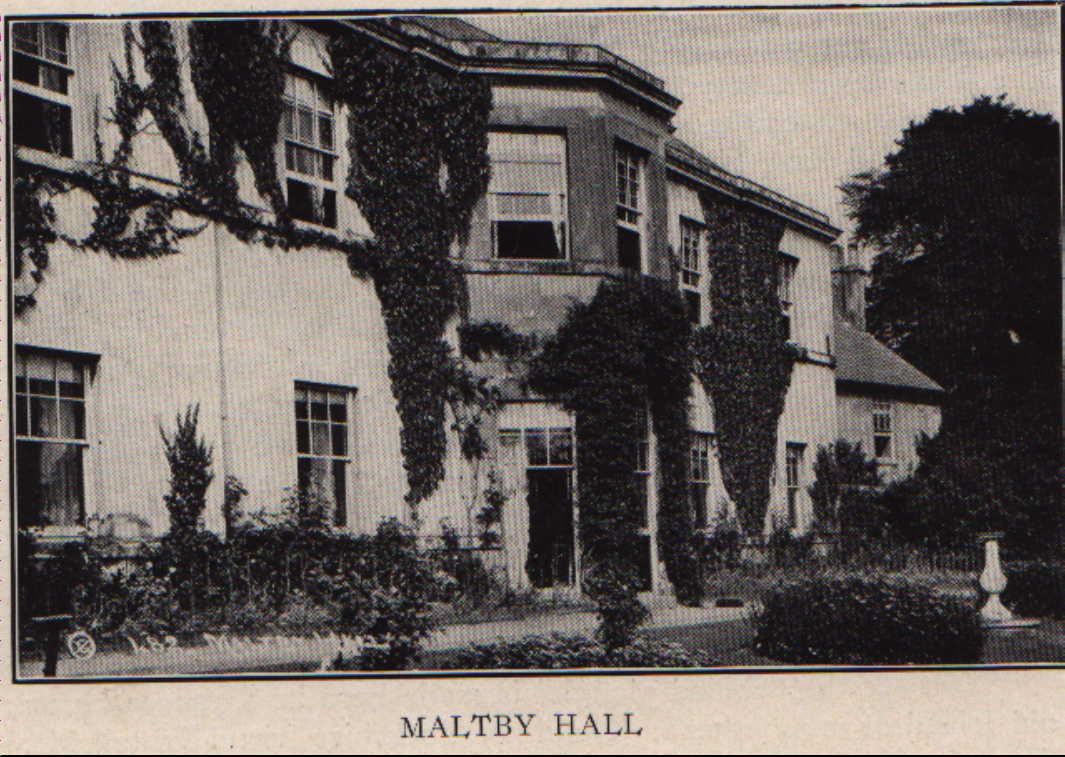

come we shall go together, mother, and hunt it all up. We next went to Maltby Hall, where now

resides Lady Violet Smithe. The Smithes,

however, were not “in residence,” so I saw only the exterior of the Hall – a

charming place, in whose gardens I tried to picture Maltbys

strolling about.

But, as interested as I was in Maltby, we “tore

ourselves away,” to drive on a mile further to “Roche Abbey, A steep, winding

roadway leads down into a valley in which stand the ruins of Roche Abbey. This is the most beautiful spot in England. It simply beggars description. Such a vale, with rocky, shaded, fern covered

banks, and broad green pastures; such myriads of wild flowers, brackets,

springs, and waterfalls, shade and sunlight, and I the midst of it all, those

grand, gray ruins. Lucky

Abbot and monks who discovered such a secluded garden of Eden in which to build

their home. Near at hand are a

few dear old cottages and in one of these, you and I are going to spend a week,

when you come to me, mother.

Enclosed is a bit of ivy I plucked from the abbey

walls. Oh, that lovely ravine, with the

cattle and sheep grazing peacefully in the meadows and within a few yards, the

old abbey mill and stone quarry!

The drive back was a quiet one, as we could think of

nothing save the beauties we had seen …. I wonder why the Maltbys

ever left so lovely a place…..

Mrs. “Eldorado has resided

abroad for some years. In 1909 she

returned to London after having made an extended trip to South Africa and

through Northern Europe. When the above

letter was written she was touring England with her husband. We regret we have not space to print two exceedingly

interesting letters written by her about Durham – its cathedral, palace,

university and the town.

In “Highways and Byways in Yorkshire,” Arthur H. Norways ways of Maltby: “Deep below the road a valley runs,

closed at length by the shoulder of a hill, on which the red-roofed village of

Maltby stands shining pleasantly in the evening sun. It is a pretty spot. The crags are fantastically piled; a few

sheep go browsing in and out among them, and from the depths of the valley,

coming out of I know not what cool region, there blows a keen and stimulating

air, growing sharper as the sn drops lower in the

sky…..”

An extract from T. Allen’s “ A

New and Complete History of the Country of York,” London, 1831. Vol. 5, pp. 193-203:

Maltby is a small parish town, situated four miles

and a half from Tickhill, and seven and a half from Rotherham. In 1821,

the population of this town amounted to six hundred and seventy-nine persons.

Maltby, in common with the great majority of our

villages, first presents itself in the pages of Domesday. We there find, that

in the time of the “Confessor, Elsi had held four carucates in Maltebi and Helgebi, and that now Roger de Busli

has five carucates in demesne and thirteen villains,

and eighteen borderers, with eighteen ploughs.

The manor of Hooton-Levit

consisted of three carucates and six borates, before

the conquest; six quaranteens in length and as many

broad. Bugo

held it. (Query: Should this not be

Hugo?) He was superseded by the Norman,

who had here in demesne one carucate and there were

eight villains and three borderers, who had three carucates. There was a mill, valued a 28d. It is now the property of the Earl of

Scarborough.

The constitution of the church of Maltby was

peculiar. The patrons presented a

rector, but the rector changed his office into a sinecure, being allowed to

nominate a perpetual vicar for the performance of parochial duties. A vicarage was ordained under the

circumstances on 12 Ral. Feb., 1240, when there was assigned for the

support of the vicar, the altarage, tithe of hay and

of the mills and four marks per annum, to be paid by the rector.

It is valued in the Liber

Regis at L4, 13s, 4d: in the parliamentary returns at L30, and is in the

patronage of the Earl of Scarborough.

The rectory was very valuable. In

Pope Nicholas Taxation, it is estimated at L26, 13s, 4d. The presentation of the vicar came, at the

dissolution, to the crown.

The church, which is dedicated to St. Bartholomew,

comprises a nave, chancel and south aisle, with a tower and spire at the west

end. It is a small and mean building,

forming a remarkable contrast to the once magnificent church of the Cistertians, who had established themselves in its

vicinity.

Note- The church has been rebuilt and restored since

this article was written.

When Dodsworth visited the

church these arms were to be seen in the windows:

Clifford. Checkie, or and az.

A fess gu. Az. A fess between three hares seiant ar. Or, on a

chevron sa. Three crescents ar. Dodsworth also transcribed

two sepulchral inscriptions which no longer remain.* * Vide South Yorkshire. Vol. I.

Near this village is the pleasant seat of J. Cook,

Esq. A school was founded here by one of

the earls of Castleton, and is repaired by his heirs.

The foundation of the abbey of Sancta Maria de Rupe, or Roche abbey, was the most splendid act of piety of

the early lords of Maltby and Hooton. But, though they were accounted the founders,

because they gave the site, the monks must have done much for themselves, and had other great benefactors.

No branch of the great Benedictine family took such

deep root in England, or flourished as luxuriantly as the Cistertian. It is an undertermined

question, which was the first monastery of this order founded in England; but

it is no question whether the house of Rievaulx,

founded by Walter Espec, was not among the first, or whether it were not the

earliest Cistertian foundation north of the

Humber. The era of its foundation

corresponds with the presidency of Harding, and the reign of Henry I. The same feeling of dissatisfaction with the

laxity of the Benedictine rule manifested itself about the same period, in the

great abbey of St. Mary, without the walls of York. Some of the monks withdraw from that house

for the purpose of submitting themselves to more austere severities, and lived

for some time under the shade of a few yew trees which grew on the banks of the

Skell. This

was in 1132. These were the small

beginnings of the house of St. Mary de Fontibus, or

Fountains. The first settlers of Kirkstall came from Fountains. Both adopted the Cistertian

habit and rule. Many other houses of

this popular order were founded in the diocese of York during that century.

The circumstances which were the immediate occasion

of the early establishment of a company of Cistertian

monks at this place have not been preserved, neither is it known from what

house the original society were a colony.

From charters preserved by Dodsworth,

it appears that in the reign of Stephen, that is, not long after the settlement

of the Cistertians at Tievaulx,

a few religious had seated themselves near the spot where afterwards the abbey

arose, and like the original settlers at Fountains, who lived for a while under

the shade of the yew trees, they appear to have assembled in this place before

any buildings were erected to receive them.

The expression which occurs in both foundation deeds, “Monachi de Rupe,” monks of the

rock, can only be interpreted upon the presumption that these sons of an

austere devotion had placed themselves in the valley, where they were screened

from the bleak winds of the north by a range of limestone rock, and were

content to practice their devotions under the open canopy of heaven.* * Hunter, Vol. I.,

266.

A natural phenomena, probably heightened by art,

contributed to induce the monks to make choice of this spot. Among the accidental

forms which portions of the fractured limestone had assumed, there was

discovered something which bore the resemblance of our Saviour

upon the cross. This image was held in

considerable reverence during the whole period of the existence of this monastery

and devotees were accustomed to come in pilgrimage to “Our Saviour

of the Roche.”

On the arrival of these monks, they were welcomed by

the two lords of the soil on which they settled themselves, Richard de Busli, the Lord of Maltby, and Richard, the son of Turquis, called also Richard de Wickersley.

To be the founders of a house of religion was a

distinction of which ever princes were ambitious; and the two lords of Maltby

and Hooton doubtless rejoiced in the opportunity

which seemed to be afforded them of connecting their names forever with such a

foundation.

By the light which the early charters afford, we

discern that there was a friendly rivalry between the two families, who should

first take the monks into their protection, and give them for their absolute

use ground necessary for their holy purposes.

It was finally arranged in a manner which must have been highly

satisfactory to the monks. The two lords

were to convey to them a considerable portion of their territory, in which was

included the rock from which they took their designation.

The Lord of Maltby’s original donation is thus

described: The whole wood as the middle

way goes from Eibrichethorpe to Lowthwaite

and so as far as the water which divides Maltby and Hooton;

also two sarts which were Gamul’s

with a great culture adjacent, and common of pasture for a hundred sheep, six

score to the hundred, is sochogia de Maltby.

The Lord of Hooton gave the

whole land from the borders of the Eibrichethorpe as

far as the brow of the hill beyond the rivulet which runs from Fogswell, and so to a heap of stones which lies in the sart of Elsi, and so beyond the

road as far as the Wolfpit and so by the head of the

culture of Hartshow, to the borders of Slade Hooton. All land and

wood within these boundaries he gave, with common of pasture through all his

lands, and fifty carectas, perhaps loads of wood in

his wood of Wickersley.

The whole of the ground comprehended in these two

donations is described in Pope Urban’s confirmation

A. D. 1186, as locum ipsum in quo abbatial sita est.* * Hunter,

Vol. 267.

Neither of these deeds has a date. But the year 1147 was assigned as the date of

its foundation, by the uniform tradition of the house.

The architecture of the portions of the building

which remain may be referred to that era.

There is such an exact conformity with the style of Kirkstall, that the church

of Roche evidently belongs to the same age, and Mr. Hunter says that it may

almost be affirmed that it was built upon a design sketched by the same

architect. It is evident, therefore that

the monks, as soon as they received the grant of the soil, set themselves about

erecting their church and apartments for their own resident. Their church was built upon an extensive and

magnificent scale, and it connot be supposed that the

burden of its erection rested solely on the lords who gave the land, though

they would, without doubt, be forward in the pious design. It is indeed one of the great difficulties

attending our monastic antiquities, to account for the command of labor, which

must have been vested somewhere, directed for the preparation of so many noble

houses of religion as arose during the twelfth century, while England was

distracted by foreign and intestine war.

The following is a correct list of the abbots of this

house:

Durandus was the first abbot. His presidency extended from June, 1147 to

1159.

Dionysius, 1159 to 1171.

Roger de Tickhell, 1171 to

1179.

Hugh de Wadworth, 1179 to

1184. He appears to have been an active

superior as in his time a confirmation from the Pope was obtained.

Osmund had a much longer presidency that anyh of his predecessors, namely from 1184 to 1223. He had been the cellarer of Fountains

abbey. In his time King Richard I,

released the house from a debt of 1300 marks to the Jews, perhaps not very

honestly.

Reginald, 1223 to 1238.

Richard, 1238 to 1254.

Walter, 1254 to 1268.

Alan, Jordan, Philip.

Thomas confessed canonical obedience to the

archbishop, 1286.

Stephen professed canonical obedience 1287.

John, 1300; Robert, 1300; William,

1324.

Adam de Gykelkwyk, 1330 to

1349. In his time the Earl of Warren

gave the rectory of Hatfield for the increase of the number of monks.

Simon de Bankewell

professed canonical obedience, 1349.

John de Aston, 1358.

Robert, 1396.

John Wakefield, 1438.

In his time Maud, Countess of Cambridge, made her will at the monastery,

and directed that her remains should be interred there.

John Gray, 1465; William Tikel,

1479: Thomas Thurne, 1486; William Burton, 1487; John

Morpetti, 1491; John Heslington,

1503.

Henry Cundel, abbot at the

time of the dissolution. The date of the

surrender is June 23, 1539. Of the

seventeen monks who joined him in the surrender, eleven were alive in 1553.

The stock of the abbey at the period of the

dissolution consisted in three score oxen, kine and

young beasts, five cart horses, two mares, one foal, one stag, sixscore sheep and fourscore quarters of wheat and

malt. The plate was very moderate.

The revenues of the house are estimated by Cromwell’s

visitors at L170 per annum and the debts are said to be L20.

Of the fabric of the abbey only a gateway, placed at

the entrance to the precincts on the side towards Maltby, and some beautiful

fragments of the transepts of the church remain. The gateway is of later architecture than the

church, indeed so late, and standing at such a distance from the monastery,

that it might be taken for part of the novum hospitum mentioned in the account of the abbey property and

which was doubtless erected by the monks for the convenience of persons

resorting to the abbey, and especially of the pilgrims who came in veneration

of the image found in the rock. A large

mass of stonework at the distance westward from the principal portion which

remains of the church, is evidently the base of one

side of the great western entrance. This

admitted to the nave, flanked by side aisles, the whole of which has

disappeared. Advancing eastward, we

arrive at the columns which supported the tower that rose at the intersection

of the nave, choir and transepts. Much

of these remain. The eastern walls of

the transepts still exist, and enough of the inner work to

show that in each were two small chapels, to which the entrance was from

the open part of the transept, and the light admitted from windows looking

eastward. In this we perceived a close

resemblance in design to the church at Krikstall

[sic], as there is also the closest resemblance in some of the minute

decorations. The difference is, that at Kirkstall (spelled

both ways in author’s copy) there are three of these chapels in each

transept. We may observe at Roche a

remarkable peculiarity respecting the Northern transept. The north wall much have arisen almost in

contact with the perpendicular rock, and indeed the whole of the northern side

of the church must have been darkened by that rock, which rises as high as the

walls of the abbey themselves. Between

these side chapels, and extending considerably beyond them, was the principal

choir, with lights at the east end and on the north and south. And with this the church appears to have

terminated, as there is nothing to indicate that there was here any lady choir

or other building beyond.

On the north side of the choir may be discerned some

rich tabernacle work a part of which has been painted of a red color.*

* Hunter’s South Yorkshire, Vol. I.

This has the appearance of having been

canopies over seats or possibly over a tomb.

The ponds in which the monks were accustomed to keep

their fish, and the mill at which they ground their corn, are

still existing.

Close adjoining to the demesnes of Roche Abbey is Sandbeck, which was once a valuable appendage to the

monastery and where is now the seat of the noble family to whom the site of the

abbey and much other property in this neighborhood belongs.

This place is not mentioned in Domesday. The land was then either lying waste or it is

included in the survey of the manor of Maltby.

It first occurs in the 6th year of the reign of Henry III.. 1224, when it is mentioned as one of the places in which

lay the six fees and a falf which Alice, Countess of Eu, released to Robert and Idonea

de Vipont.

Arthur H. Norway in “Highways and

Byways in Yorkshire.” Writing of Roche Abbey says: “This path descends in to the valley of a

little river by whose bank, half buried in the greenery, stands the stately

gatehouse of Roche Abbey, set close beneath the precipice from which the monks,

seizing the most striking feature of their valley with that quick sense of picturesqueness which distinguished the

Cistercians, named themselves “monachi de rupe,’ Monks of the Rock. . . The warm glow of the afternoon falls into the

valley in a flood. The little stream

gleams with its reflection as it steals along beneath the trees. In an open glade a trifle

higher up a couple of red-roofed cottages stand shining in the sun, and

the fowls go to the fro clucking in the short grass. In the abounding stillness one might fancy

that all human life had ceased on the departure of those who planned and built

the lovely walls which are now a shattered ruin, waiting in some enchanted

slumber till their master’s hand shall set them up once more in their ancient

glory, and the sound of chanting roll again through the hollow and over the

short turf on the limestone crags above.

I sit down in the shadow of the bank and rest awhile in this, the

loveliest spot I shall see today.”